History of manufacturing at Cambridge

It seemed, then, an opportune moment to pause and reflect on how we have got here. As with all such endeavours, the journey has been part strategic and part serendipitous but underpinning it all has been a commitment to furthering our knowledge of manufacturing in its broadest sense, and passing that knowledge on to industry and government and to successive generations of talented students.

In many respects, the IfM is following in the footsteps of James Stuart, the first ‘true’ Professor of Engineering at Cambridge (1875-1890). An educational innovator and a passionate advocate of putting theory into practice, he challenged the conventions of his day. When faced with what he considered to be inadequate teaching facilities, undeterred he created a workshop for his students in a wooden hut and, less popularly, installed a foundry in Free School Lane. The story of manufacturing at Cambridge is imbued with his indomitable spirit.

|

|

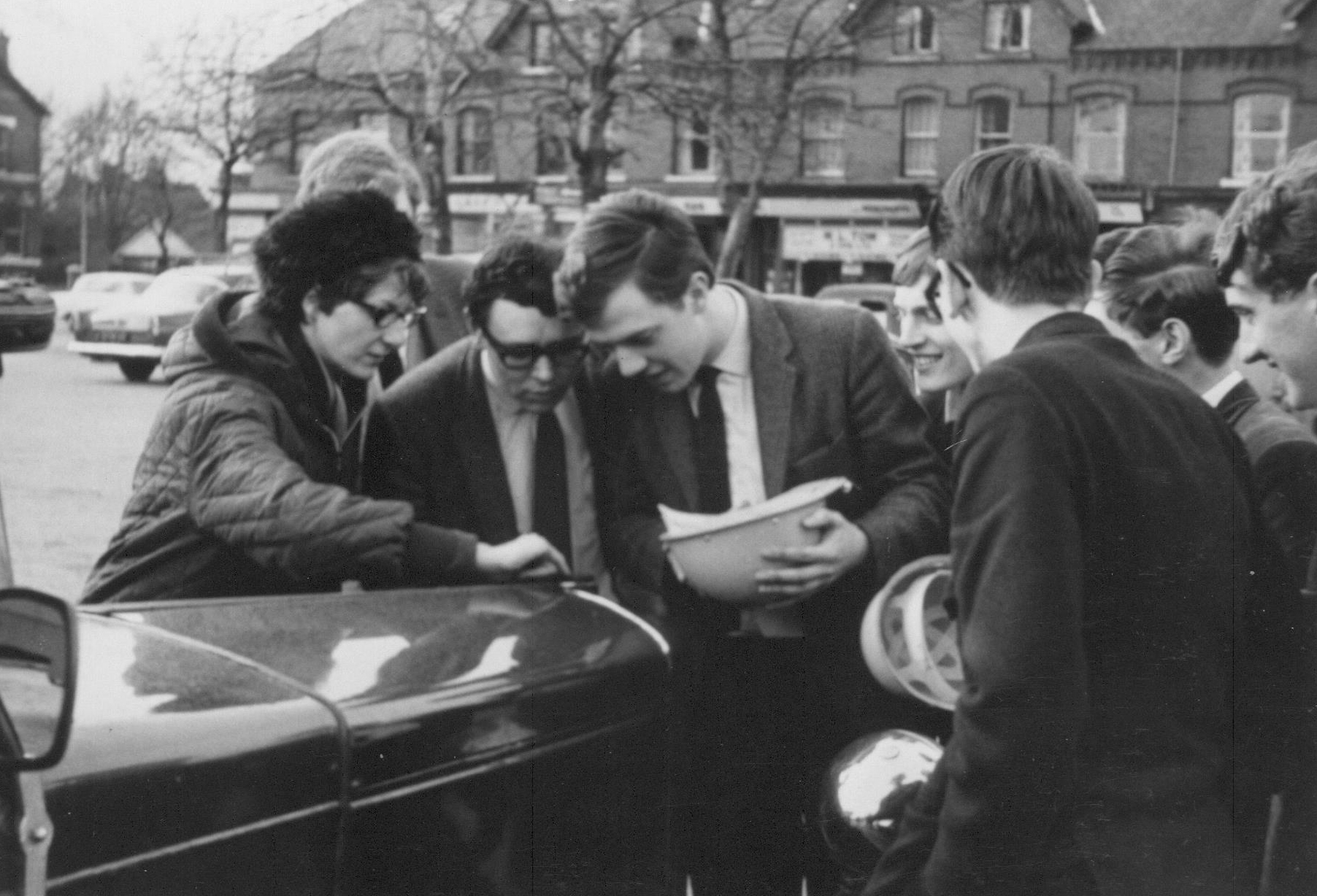

1966: students on the first Advanced Course in Production Methods and Management (now the MPhil Industrial Systems, Manufacture and Management) |

THE 1950s, 60s AND 70s

The start of manufacturing education in Cambridge: the Advanced Course in Production Methods and Management.

In the 1950s Britain was still an industrial Goliath. Manufacturing accounted for around a third of the national output and employed 40 per cent of the workforce. It played a vital role in rebuilding postwar Britain but for a number of reasons – including a lack of serious competition and an expectation that it would provide high levels of employment – there was little incentive for companies to modernise their factories or improve the skills of their managers and workers.

In those days, it was the norm for engineering graduates to go into industry as ‘graduate apprentices’ for a period of up to two years. In practice, this was often badly organised, resulting in disappointment and frustration for all concerned.

Sir William Hawthorne, Professor of Applied Thermodynamics (and later Head of Department and Master of Churchill College), was himself an unimpressed recipient of graduate training. He likened apprenticeships to an unpleasant initiation ritual “in which people had their noses rubbed in it and then rubbed other peoples’ noses in it.” Even if you were lucky enough to avoid having your nose rubbed in anything, your apprenticeship probably involved “standing next to Nelly and watching what they did”. Hawthorne could see that this approach perpetuated current practice and inhibited innovation and entrepreneurship.

He decided that Cambridge could – and should – do something about it and asked his colleagues John Reddaway and David Marples to devise some short industrial courses for graduates. These comprised lectures, discussions and site visits and looked at how a whole company operated – how it organised its engineering design, production control, welfare and marketing. And the courses seemed to work. They were run very successfully for the aircraft engine manufacturer, D. Napier & Son Ltd. and based on this experience, Reddaway, Marples and Napier’s head of personnel J. D. A. Radford, wrote a paper on “An approach to the techniques of graduate training”. They presented this paper to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1956 with the suggestion that it would take over the running of these courses and make them widely available. Although the courses – and the paper – were well received, with no sense of urgency over the need to improve current practice, the enterprise succumbed to a lack of funding. In the meantime, Reddaway had been asked by the University to produce a plan for a course similar in style and content that would last a year. This became known as the Reddaway Plan. But there was no money to recruit someone to run it so the plan gathered dust for the best part of ten years.

During those ten years concern was beginning to mount over Britain’s lagging productivity and its declining share of world export markets. Successive governments embarked on a series of policy interventions and manufacturing became something of a national preoccupation. When John Reddaway was asked to talk about his plan at a conference of the Cambridge University Engineering Association in 1965, there was perhaps a greater imperative for change. In attendance was Sir Eric Mensforth, the Chairman of Westland Aircraft. Coincidentally, Reddaway had been an apprentice at Westland and when Mensforth established a scholarship at Cambridge, Reddaway had been its first recipient. Mensforth offered the University £5,000 if they could get the Reddaway Plan off the ground.

Also in the audience was Cambridge alumnus, Mike Sharman, who immediately volunteered to leave his lectureship at Hatfield Polytechnic to run the course, even though Mensforth’s contribution amounted to just two years’ worth of funding.

The Advanced Course in Production Methods and Management was up and running the following year, with its first intake of 12 students. Lasting a full calendar year, and designed to emulate professional rather than student tasks and disciplines, the course involved an intense series of real two-to-three week projects in factories across the country, interspersed with lectures from practitioners as well as academics.

The projects, typically analysing and improving factory operations, were almost always successful – sometimes spectacularly so. Industry responded well to seeing these students getting to grips with the practicalities of engineering and manufacturing and graduates from the course were, and continue to be, much in demand. The notion that going into a factory and undertaking short, intensive projects would be an effective way of learning was nothing short of and gave them the confidence to tackle increasingly difficult tasks, developing them very rapidly into people who really could go on to become ‘captains of industry’.

Mike Gregory took the course in its fourth year: “For many of us who were introduced to the world of engineering and manufacturing through the ACPMM, the experience was quite literally life changing. We students were swept along by Mike Sharman’s enthusiasm, not to mention the thrill of travelling around the UK and overseas, visiting and working in all manner of factories. How to make a Volkswagen Beetle, how to make a tennis racket, how to put the flavour on both sides of a potato crisp – we learnt all this and much, much more.”

In 1987 a design option was added to ACPMM and it changed its name to the Advanced Course in Design, Manufacture and Management (ACDMM). This was in response to the growing recognition of the importance of design as a competitive differentiator.

But the path of ACPMM/ACDMM did not always run smooth. For many years the course occupied an anomalous position within the University, which remained suspicious of it and would periodically try to close it down. Until 1984, when Wolfson College agreed to take it in, it did not have a proper University home which meant the students were not members of the University. Funding was a perpetual problem, particularly when universities were required to be more accountable for their spending. For many years, ACPMM did not have a qualification attached to it and the University Grants Committee (UCG) would only fund universities on the basis of the numbers of students who were awarded degrees or diplomas.

|

|

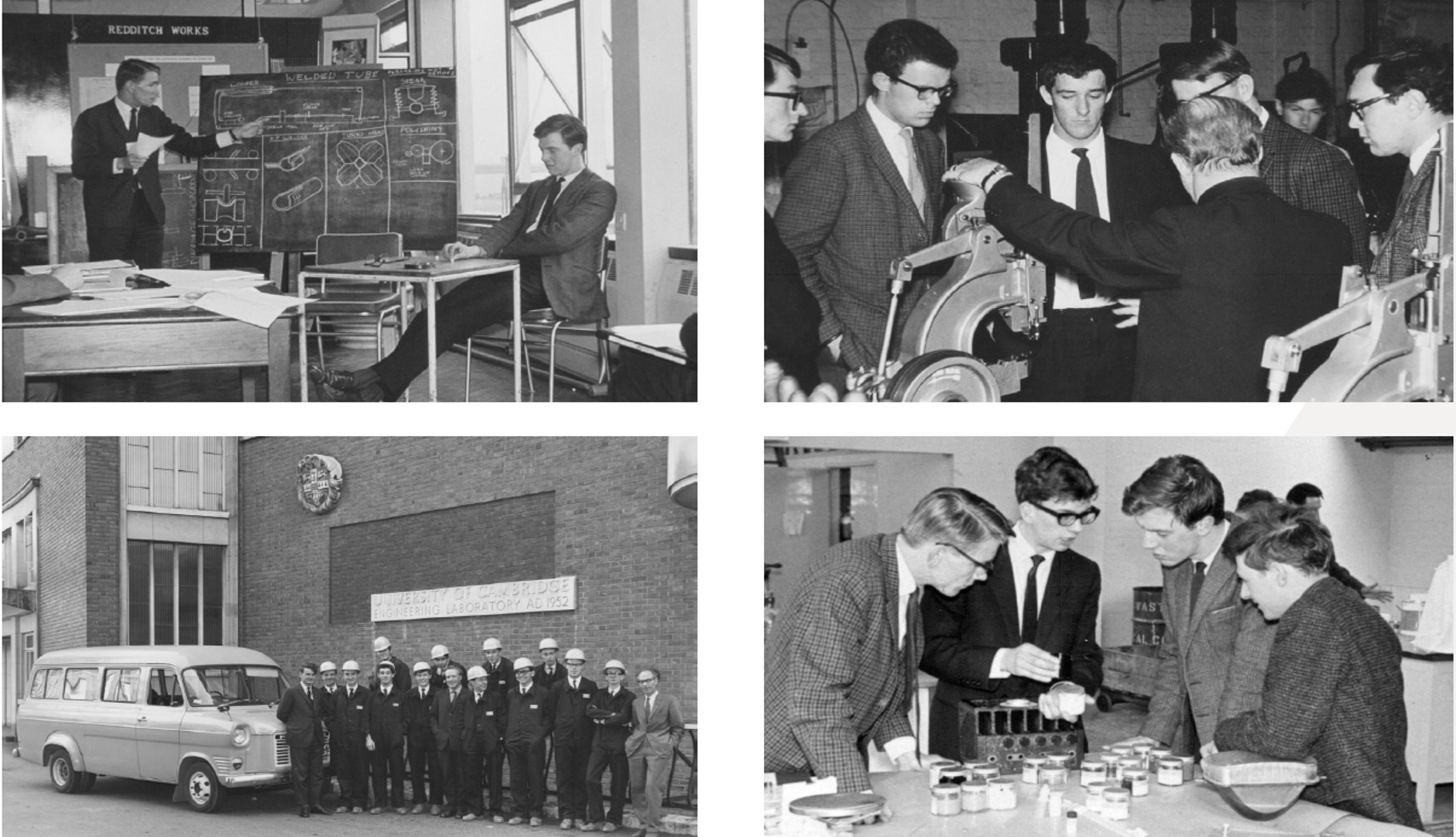

The first year of ACPMM |

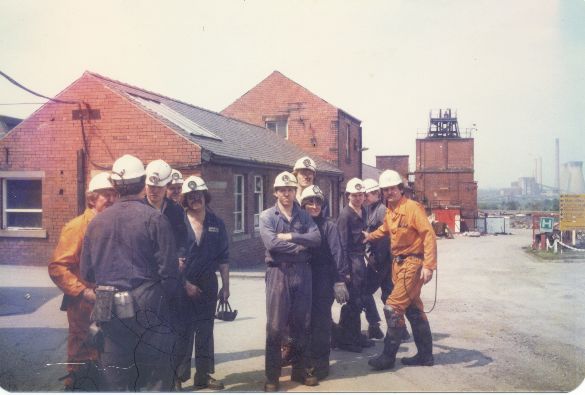

Another unusual aspect of the course was that in the 1970s it developed relationships first with the University of Lancaster and then Durham as a way of both expanding its teaching expertise and extending its geographical reach into companies the length and breadth of Britain. This became an additional complication when funds began to be allocated on the basis of student numbers and the administrative task of sharing the funding equitably between the partners proved to be too difficult to resolve. In 1996 Cambridge was left to forge ahead on its own.

|

|

Year 17 ACPMM students emerging from a mine |

The qualification problem was solved when Professor Colin Andrew arrived in the mid-80s and set about devising an examination which would allow for the awarding of a diploma. He managed to persuade both Mike Sharman and the University that this was a good thing to do. But as one hurdle was surmounted another would appear. Other funding shortfalls emerged as the awarding bodies offered fewer studentships and cut support for staff. In this not entirely conducive environment, ACDMM was looking to increase its student numbers. At this point, David Sainsbury (now Lord Sainsbury of Turville and Chancellor of the University) and the Gatsby Charitable Foundation intervened. The continuation of ACDMM was consistent with one of Gatsby’s primary charitable objectives – to strengthen science and engineering skills within the UK – so Gatsby agreed to provide funding for a five-year period.

Mike Sharman finally retired in 1995, having been awarded an MBE the previous year for his endeavours. Tom Ridgman arrived from the University of Warwick with a 20-year career in the automotive industry behind him and took over as Course Director in 1996. In 2004, still facing funding challenges and after a thorough review of the options, the course was renamed again – Industrial Systems, Manufacture and Management (ISMM) – and became an MPhil. It was reduced to an intensive nine months, concluding with a major dissertation. This resulted in an immediate increase in student numbers and the course today, under the stewardship of Simon Pattinson, is oversubscribed by a factor of five, and attracts candidates of an exceptionally high calibre from all over the world.

|

|

Recent ISMM students on an overseas study tour |

A new course for undergraduates: Production Engineering Tripos

In the 1950s and 60s an undergraduate degree in engineering at Cambridge was all about science and mathematics – management was very much the poor relation. David Newland, who went on to be Head of Department between 1996 and 2002, recalls that as an undergraduate in the 1950s there were just two lectures a week on management, timetabled for Saturday mornings, “which was when most people played sport and, in any case, there was a perception that you could just waffle your way through the exam questions.” By the 1970s, Britain’s manufacturers were seeing their share of global export markets continue to decline and were facing an array of domestic challenges, not least in the area of labour relations.

Governments continued to pursue industrial policies and announced that the University Grants Commission would consider applications for a four-year engineering degree course rather than the conventional three years, as long as the focus was on preparing graduates for industry rather than research. The Department of Engineering responded with a proposal, which was accepted, to establish the Production Engineering Tripos (PET). This was a first for Cambridge: it allowed engineering students to specialise for their last two years in learning about manufacturing both from an engineering and a management perspective. The intention was to equip these very bright students with the theoretical and practical knowledge and ability to solve real industrial problems – and the skills and experience to hold their own in a factory setting.

Mike Gregory who had been recruited in 1975 by Mike Sharman to work on ACPMM moved across to set up the new PET course. In 1988 PET changed its name to Manufacturing Engineering Tripos (MET) to reflect the breadth of its approach. From the early days of John Reddaway’s short courses there had been a recognition that manufacturing was concerned with much more than just ‘production’ and encompassed a range of activities which included understanding markets and technologies, product and process design and performance, supply chain management and service delivery.

|

|

Mike Gregory and MET students on the overseas |

By 1997 Mike, as we shall see, was increasingly busy and passed the running of the course on to Ken Platts. Ken steered MET through its first teaching quality assessment before handing it over first to Jim Platts and then to Claire Barlow who ran it successfully for many years. Today’s MET students, like ‘ISMMs’, are very much sought after and the course has produced a string of distinguished alumni who have launched successful start-ups, transformed existing manufacturing organisations, developed new technologies and delivered a wide range of new products and services around the world.

THE 1980s AND 90s

Research and practice go hand in hand

During the 1980s and 1990s UK manufacturing continued to shrink as a proportion of national output. But if manufacturing in the UK was in decline, it was proliferating in both scale and complexity elsewhere. Japan, in particular, was combining automation with innovative working practices and was achieving spectacular results both in terms of quality and productivity. Manufacturers of all nationalities were going global, building new factories in developing countries giving them access both to rapidly growing new markets and cheaper sources of labour. Now manufacturers were in the business of managing interconnected global production networks and taking an even broader view of their role – subcontracting parts of their operation to other businesses.

While large companies were becoming increasingly international, entrepreneurship was thriving close to home. The ‘Cambridge Phenomenon’ – a cluster of technology, life sciences and service-based start-ups – was underway and beginning to attract the attention of researchers.

When Colin Andrew was appointed as Professor of Mechanics in 1986, the name of the chair, at his request, was changed to Manufacturing Engineering. This signalled a new direction for the Department and a growing recognition that manufacturing was an important subject for academic engagement. Around the same time, Mike Gregory admitted to harbouring an ambition to establish a manufacturing institute. Colin was sympathetic to the idea, but counselled that a convincing academic track record was a prerequisite for such a task. With characteristic energy, Mike took up the challenge and set about developing a set of research activities which would reflect the broad definition of manufacturing that was already informing both undergraduate and postgraduate teaching.

Ten years later the foundations were in place. In 1994, on Colin Andrew’s retirement, Mike was appointed as Professor of Manufacturing and Head of a new Manufacturing and Management Division within the Department of Engineering. An embryonic Manufacturing Systems Research Group was beginning to make a name for itself. Had James Stuart been around, he would have recognised a fellow unstoppable force.

Management research

Following a series of industrial and academic consultations in 1985 and 1986 an EPSRC Research Grant, Manufacturing Audit, was won. It explored how manufacturing strategies might be understood and designed in a business context. The recruitment of Ken Platts from TI’s research labs in 1987, and his pursuit of the project as a PhD topic, resulted in a sharper academic focus and the publication of a workbook on behalf of the Department for Trade and Industry, Competitive Manufacturing: a practical approach to the development of manufacturing strategy.

Ken’s appointment was important in a number of ways. It established the precedent for bringing in people with industrial experience to research posts and it embedded the principle that manufacturing research at Cambridge should be useful for industry, both in its subject matter and in its outputs. The workbook became the blueprint for a distinctive way of working. For each major research project, a book would be produced that would give managers working in industry a set of tools and approaches they could apply themselves. The fact that this first attempt went on to sell in the region of 10,000 copies was also helpful in establishing Cambridge’s credentials.

Ken’s work demonstrated the potential for taking an ‘action research’ approach to management. In other words, instead of relying on surveys and case studies, important though these were, the researchers would take their theoretical models into companies and test them in real-life situations. This strand of research led to the Centre for Strategy and Performance and established an approach that would be widely adopted across the IfM. Ken’s early work also attracted funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. This large, rolling grant enabled the recruitment of additional researchers, including one Andy Neely, and established Cambridge as a serious player in the field of manufacturing strategy and performance measurement.

The next key research appointment was of David Probert in 1992, another ACPMM alumnus who, like Ken, came from industry. Building on the foundations laid by Mike and Ken in manufacturing strategy, David identified and focused on what was becoming an increasingly common conundrum: whether a manufacturer should make a product or part itself, or outsource it to a supplier. David’s work in this area gained immediate traction with companies and his framework was adopted by Rolls-Royce amongst others. This led directly to EPSRC-funded work on technology management which has since developed into a highly successful and wide-ranging research programme. A principal focus has been on creating robust technology management systems to help companies turn new ideas into successful products and services. This work coalesced around five key processes: how to identify, select, acquire, exploit and protect new technologies. Strength in this area was bolstered by the addition of James Moultrie’s expertise in industrial design and new product development, and, more recently, by the arrival of Frank Tietze with his research interest in innovation and intellectual property. Research into widely applicable business management tools has also emerged as a fruitful area of investigation, with Rob Phaal establishing the IfM as a centre of expertise in roadmapping.

Much of this research activity has been most applicable to large and mid-size companies but there has also been significant interest in more entrepreneurial technology-based activities, not least those taking place in the ‘Cambridge Cluster’ and the challenges inherent in trying to commercialise new technologies. This work was pioneered by Elizabeth Garnsey in the 1980s and is continued by today by Tim Minshall and his Technology Enterprise Group.

In 1994 Yongjiang Shi joined this small band of researchers to start his PhD on international manufacturing networks. This was the beginning of a whole new research strand which initially focused on ‘manufacturing footprint’. Its groundbreaking work in this area led to a major collaboration with Caterpillar and the IfM’s Industry Links Unit (more of which later) and the development of a set of approaches that would help multinational companies ‘make the right things in the right places’. As international manufacturing has become increasingly complex and dispersed, the research, under the leadership of Jag Srai, has broadened to encompass end-to-end supply chains, designing global value networks and creating more resilient and sustainable networks. As with the early work on manufacturing footprint, this new research is carried out in partnership with industrial collaborators.

Technology research

Significant progress had been made in management and operations research when Duncan McFarlane joined the fledgling Division in 1995 bringing his expertise in industrial automation and adding an important technical dimension to the team. Duncan went on to establish the Cambridge Auto-ID Lab, one of a group of seven labs worldwide, leading work on the tracking and tracing of objects within the supply chain using RFID. It was this group that coined the phrase the ‘internet of things’ and has gone on to lead research in this area. Duncan’s team subsequently expanded to encompass a wider range of interests, looking at how smart systems and smart data both within factories and across supply chains can be used to create more intelligent products and services. Ajith Parlikad’s work on asset management has become a key part of this research programme and is also integral to the innovative work Cambridge’s Centre for Smart Infrastructure and Construction is doing to improve the UK’s infrastructure and built environment.

|

|

Installing robots in Mill Lane |

Production processes were clearly an important topic for a manufacturing research programme and a new group drawing on work from across the Division was set up to address it in the late 1990s. In 2001, GKN funded a new chair in Manufacturing Engineering to which Ian Hutchings was appointed. Ian came from the Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy and had an international reputation for his work in tribology. He further developed the Production Processes Group, which brought together a number of research activities including Claire Barlow’s work on developing more sustainable processes. In 2005, Ian set up the Inkjet Research Centre with EPSRC funding to work with a group of UK companies, including a number in the local Cambridge cluster, to carry out research both into the science behind this important technology and its use as a production process.

In 2003, Bill O’Neill had joined the IfM from the University of Liverpool, bringing with him his EPSRC Innovative Manufacturing Research Centre (IMRC) in laser-based micro-engineering. This became the Centre for Industrial Photonics which is now, with Cranfield University, home to the EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Ultra Precision and the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Ultra Precision. Both the Distributed Information and Automation Laboratory and the Centre for Industrial Photonics have been able to commercialise their intellectual property through spin-outs, the former setting up RedBite, a ‘track and trace’ solutions company and the latter, Laser Fusion Technologies which uses laser fusion cold spray technology for a wide range of energy, manufacturing and aerospace applications.

A new identity

Mike’s ambition to create a manufacturing institute finally came to fruition in 1998 when an alliance was forged with the Foundation for Manufacturing and Industry (the FM&I). This was an organisation set up to help companies understand how economic and policy considerations would affect their businesses and to enhance the public profile of manufacturing in the UK. It brought with it a large network of industrial partners and complemented the Division’s now considerable strength and breadth in manufacturing and management research and its embryonic Industry Links Unit (see below). The Institute for Manufacturing was born, embedded in the Engineering Department’s Manufacturing and Management Division but with a distinct character and set of capabilities which enabled it to address the challenges manufacturers were facing – and the policy context in which they were operating.

Policy research

One of Mike’s aspirations for the new Institute was to use its manufacturing expertise – both strategic and technical – to support government thinking and to raise awareness of the continued importance of manufacturing in the context of an increasingly service-oriented economy. The merger with the FM&I added an economics and policy dimension to the IfM. This would develop into an important research strand asking the fundamental question: why are some countries better than others at translating scientific and engineering research into new industries and economic prosperity? The IfM’s policy research team, founded by Finbarr Livesey and today led by Eoin O’Sullivan, is very actively engaged with the policy community in addressing these questions (see page 6).

As with all IfM undertakings, the intention was that research in this area should prove useful. It is based, therefore, on practical engagement with policymakers to understand their needs and provide outputs which support them in their decision-making. In 2003, Mike also established the Manufacturing Professors’ Forum, an annual event which brings together the UK’s leading manufacturing academics, industrialists and policymakers to develop a shared understanding of how to create the conditions in which UK manufacturing can flourish.

|

|

Farewell to Mill Lane |

Putting research into practice

That notion that the research carried out at the IfM should be of real value to its industrial and governmental collaborators was enshrined in the creation of an Industry Links Unit (ILU) which had been set up in 1997, a year before the IfM came into being. At that time, stimulating fruitful collaborations between universities and industries was not a priority for public funding. The Gatsby Charitable Foundation, which had previously played a critical part in sustaining ACPMM through tricky financial times, believed that fostering such interactions was key to developing long-term economic growth – and that the proposed new unit could have a useful part to play in this regard. It provided initial funding for the ILU which allowed it to develop the three main strands of activity designed to facilitate the transfer of knowledge: education, consultancy and publications. Gatsby also encouraged the ILU to put itself on a clear commercial footing by setting up a separate, University-owned company (Cambridge Manufacturing Industry Links or CMIL) through which it could generate income from the ILU’s activities to fund future research.

CMIL was successfully nurtured through its early years first by John Lucas and then by Paul Christodoulou. In 2003, Peter Templeton was recruited as Chief Executive and by 2009 the range and scale of its activities had grown to such an extent that the decision was taken to merge ILU and CMIL into IfM Education and Consultancy Services Limited. This created a clearer organisational structure and a name that ‘does what it says on the tin’.

Education services

CMIL aimed to transfer knowledge and skills to people working in industry through a variety of courses, some of which were one- or two-day practical workshops while others were longer programmes such as the Manufacturing Leaders’ Programme, a two-year course for talented mid-career engineers and technologists who had the potential to move into more strategic roles in industry. In 2006, CMIL set up an MSc in Industrial Innovation, Education and Management for the University of Trinidad and Tobago which ran very successfully until 2013 and demonstrated a capability for exporting IfM educational practice. Creating customised courses for very large companies was – and continues to be – an important activity.

Consultancy Services

By appointing ‘industrial fellows’, many of them alumni of ACPMM and MET, CMIL was able to establish a consultancy arm which could disseminate and apply the IfM’s research outputs to companies of all sizes, from multinationals to start-ups and with national and regional governments. Initially, much of the focus was on small and medium sized manufacturers which, according to former Chairman and CEO of Jaguar Land Rover and longstanding friend and advisor to the IfM, Bob Dover, had been largely neglected by academics. The intention was to give an academic rigour to the decisions the companies were taking, underpinned by research from the Centre for Strategy and Performance. This led to the development of ECS’s ‘prioritisation’ tool which has now been used with more than 750 companies and its ‘fast-start’ approach to business strategy development.

The consultancy programme has grown steadily in recent years, delivering projects which have had a real impact on the organisations concerned and the wider manufacturing environment. IfM ECS, for example, has facilitated many of the roadmaps which define the vision and implementation plans for new technologies in the UK, such as synthetic biology, robotics and autonomous systems and quantum technologies. In 2012, it was commissioned by the Technology Strategy Board (now Innovate UK) to carry out a landscaping exercise looking at opportunities for high value manufacturing across the UK. It is currently engaged in ‘refreshing’ the landscape to establish clear priorities for the government and, in particular, to identify areas where investment in manufacturing capabilities can be maximised by co-ordinating the efforts of delivery agencies.

IfM ECS also carries out a wide range of research-based consultancy activities with companies, including major projects with multinationals to redesign their production networks or end-to-end supply chains. It works with companies of all shapes and sizes to align their technology and business strategies and help them turn new technologies into successful products or services.

2000s AND 2010s

Rapid expansion – and a new home

Since 2000, the manufacturing landscape has changed very rapidly. Disruptive technologies and new business models present threats and opportunities which industry and governments need to understand, and act upon. An increasingly pressing concern is how we can continue to satisfy the world’s appetite for products and services without destroying the planet in the process.

|

|

The proposed position of the new building on the West Cambridge site |

As we have already seen, research, education and practice at the IfM were expanding at speed as we entered the new millennium. In 2001 the IfM was awarded a major grant and became home to one of the EPSRC’s flagship Innovative Manufacturing Research Centres which, when joined with Bill O’Neill’s IMRC in 2003, created an organisation of significant size and scope. However, it was operating out of a rather ramshackle set of offices and laboratories in Mill Lane in the centre of Cambridge and this was becoming a limiting factor, to the extent that the new photonics team was exiled to the Science Park.

A fundraising campaign raised £15 million from a number of very generous benefactors, including Alan Reece through the Reece Foundation, and the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, which was enough to build the IfM a new home. In 2009, it moved to its current purpose-built premises on the West Cambridge site. This was a hugely significant development, not only from the perspective of staff comfort and morale. It meant the IfM could host a whole range of events and activities which were useful in themselves but also gave more and more people a glimpse of the work going on there and led to further interest in research collaborations and consultancy projects.

|

|

19 November 2009: the Duke of Edinburgh unveils the plaque at the opening of the new building, applauded by Dame Alison Richard, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge at the time. |

The new building also enabled further expansion of the research programme, through increased office space and laboratory facilities. In 2010, Professor Andy Neely returned to the IfM from Cranfield – having worked with Ken Platts on performance measurement in the 1990s – to found the Cambridge Service Alliance, which brings together academics and multinational companies to address the challenge an organisation faces when moving from being a maker of products to a provider of services.

A cross-disciplinary Sustainable Manufacturing Group had been operating at the IfM since the late 1990s and developing sustainable industrial practice has been a common thread running through the IfM’s various research programmes. In 2011 this was given a significant boost when the EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Industrial Sustainability led by Steve Evans was established within the IfM. This is a collaboration between four universities (Cambridge, Cranfield, Imperial College, London and Loughborough), with a membership programme to ensure manufacturing businesses both help set the research agenda and actively participate in its projects.

Understanding business models is at the heart of many of the IfM’s research activities: how can a company add a example, or learn to operate in a more sustainable way? What impact will new technologies such as 3D printing have on both established firms and new market entrants? How should businesses redesign their operations networks in response to disruptive technologies? Chander Velu has set up a new research initiative which takes a management and economics approach to business model innovation and aims to bring together different perspectives from across the IfM and key UK and international universities to establish a co-ordinated research agenda.

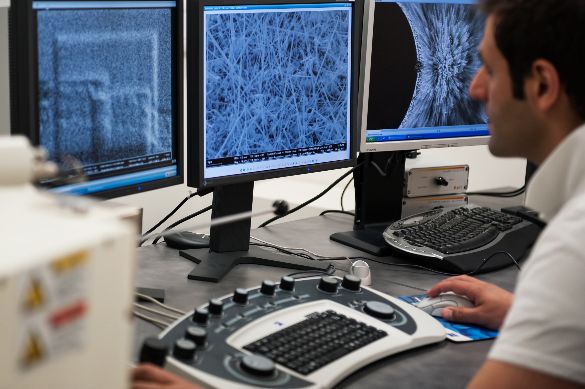

More lab space has allowed the IfM to extend its science and technology research interests, recently acquiring multidisciplinary teams looking at how to manufacture new materials at scale, such as carbon nanotubes (see page 9) and biosensors, led by Michaël De Volder and Ronan Daly respectively. By working with colleagues with policy, management and operations expertise, these teams are able to address the scientific and technological challenges within the broader context of the manufacturing value chain in order to understand the risk factors early on and maximise the chances of successful commercialisation.

|

|

IfM common room – a space designed to encourage networking and collaboration. |

IfM ECS has continued to expand the range of services it offers. For example, it is currently running a bespoke executive and professional development programme for Atos (see page 27) and is actively expanding its portfolio of open courses and workshops to reflect new research emerging from the IfM’s research centres. Similarly, the number of tools and techniques IfM ECS has at its disposal to support industry and government through consultancy is growing to encompass activities such as product design and servitization.

In 2010 IfM ECS took on the management of ideaSpace, an innovation hub in Cambridge which provides flexible office space and networking opportunities for entrepreneurs and innovators looking to start up new, high impact enterprises. As well as helping to create successful new businesses and economic value, ideaSpace also works with governments, agencies and universities to develop policies, strategies and programmes which support a thriving start-up sector.

|

Taking stock

Manufacturing research, education and practice at Cambridge have come a long way in the last 50 years but they still remain true to the vision of Hawthorne and Reddaway: manufacturing is about much more than shaping materials. To understand the complexities of modern industrial systems with their engineering, managerial and economic dimensions you need to be fully engaged with the people and companies that do it ‘for real’. The research programme here is now extensive, covering the full spectrum of manufacturing activities. This year the University of Cambridge as a whole received more EPSRC funding for manufacturing research than any other UK university. IfM has an important role to play not only in doing its share of that research but in facilitating manufacturing research across the University.

Education is thriving. The ISMM and MET courses go from strength to strength and this year we have more than 75 students doing PhDs or research MPhils.

IfM ECS continues to grow, putting IfM research into practice whether redesigning multinational companies’ operations networks, helping to develop robust innovation and technology strategies and systems, or delivering executive and professional development programmes and open courses.

|

|

Using the scanning electron microscope in the Centre for Industrial Photonics |

Looking to the future

So where will the next 50 years take the IfM? Our strong sense of purpose will not change – we remain committed to making a difference to the world by improving the performance and sustainability of manufacturing. We will continue to create knowledge, insights and technologies which have real value to new and established manufacturing industries and to the associated policy community. And we will continue to ensure that our knowledge has an impact, through our education and consultancy activities.

|

|

James Moultrie inspiring recent MET students |

But the IfM is fundamentally about innovation. So while we will carry on doing what we do best, we will also look for opportunities to do things differently. We have ambitious plans for the future which include the possible development of a ‘scale-up centre’, a physical space devoted to supporting the transition of ideas and concepts from lab-based prototypes into scalable industrial applications. James Stuart would have approved of the energy and determination that has gone into creating the IfM as we know it today and his pioneering spirit will continue to inspire us. This way we hope to ensure that the next 50 years are even more productive and enjoyable than the last 50.

This article was written by Sarah Fell based on interviews conducted by IfM doctoral students Chara Makri, Katharina Greve and Kirsten Van Fossen with members of staff past and present and with long-standing friends of IfM.