Twenty-first century supply chains: Transforming the pharmaceutical industry

The Centre for International Manufacturing (CIM) is leading the research programme in REMEDIES, a £23m sector-wide initiative to understand how pharmaceutical supply chains in the UK are set to change. Dr Jag Srai, Head of CIM, considers the implications for government, industry, healthcare providers – and patients.

The internationalisation of supply chains through offshoring, outsourcing and the need to access new markets has brought with it complexity, risk and sustainability challenges. Indeed, many firms are faced with rethinking their supply chain footprint and are considering whether more local supply chains may better serve the more demanding 21st century consumer. New technologies are also helping companies meet the needs of more niche markets and customers, as demonstrated by the rapidly evolving pharmaceutical sector.

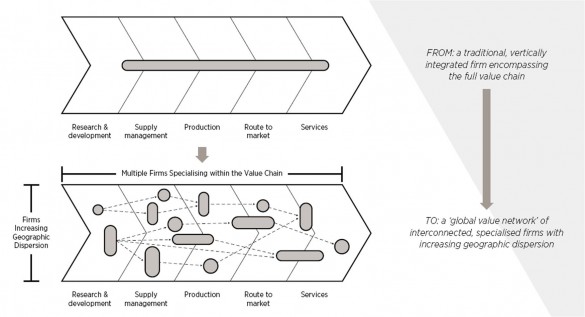

In the 1990s supply chains were more transparent, based on local suppliers serving established markets. Most multinational companies would carry out and, therefore, control everything from research and development, through all aspects of the physical supply chain – procurement, production and distribution – to marketing and after-sales services. The situation today could not be more different. Supply chains have been transformed into complex global value networks as multinationals have increasingly focused on what they are good at and outsourced everything else to specialist companies with technical expertise in a particular area – often bringing with them the advantages of lowcost labour. The typical supply chain for industry sectors such as pharmaceuticals now involves hundreds of these kinds of specialist firms. So multinationals need to find ways to design and manage these large and complex networks to maximise their competitive advantage. And that task has to be carried out in the context of the wider industrial landscape which itself is subject to continuous change in its market, technological and geopolitical conditions.

In simpler times, multinationals were able to concentrate on continuous improvement programmes, many of which achieved impressive results in terms of better inventory management, greater speed to market and reduced plant downtime. However, these new highly distributed networks have made the continuous improvement task harder and the challenge of managing these operations is fundamentally redefining 21st century supply chain thinking. It is now vital for companies to understand and analyse the broader supply network and not just the ‘tier one suppliers’ (organisations with whom they deal directly) but also the tier two suppliers who supply the tier ones and further on down through the increasing levels of specialisation. Companies now need to look at their extended (or ‘end-to-end’) supply chain beyond their traditional boundaries to assess the effectiveness of the network as a whole.

Pharmaceutical companies are a good example of this new paradigm. The context in which they operate is changing. These days, patient outcomes and compliance with treatment regimes are paramount: it’s no longer just about delivering products on-time, in-full to a distributor. Patient expectations, in both developed and emerging markets, are changing – they want instant access to more affordable and, where appropriate, more personalised products.

Patient expectations, in both developed and emerging markets, are changing – they want instant access to more affordable and, where appropriate, more personalised products.

New diagnostic technologies are also being developed which have the potential to recognise the patient – rather than the healthcare provider – as the ultimate consumer and to service their needs more effectively. These new remote patient management diagnostic tools and ‘apps’ will be integrated within sophisticated IT systems to monitor patients and, potentially, to order personalised solutions for them.

At the same time, new technological developments in manufacturing processes mean that the industry is poised to switch from its current batch-processing model to a continuous manufacturing process. Interestingly, the emergence of this new technology has been informed at least as much by the industrial supply chain opportunities it might deliver as the potential benefits it has for product functionality. Traditionally, production processes were seen solely as the purview of the R&D and process engineering teams with very little input from further down the value chain, except in modest ways such as specifying improvements to the stackability of products on pallets or in containers.

Recent research, however, suggests that the supply chains themselves are starting to redefine both product design and the production technology used to manufacture pharmaceuticals. This proactive approach is resulting in the development of advanced production facilities that can deliver new and different options in terms of scale, flexibility and variety as companies strive to better serve the needs of the end-user.

From the companies’ perspective there are major supply chain gains to be had from continuous manufacturing, including a reduction in inventory levels, better quality assurance, greater flexibility in adjusting production volumes, and perhaps the ability to recycle chemicals within agreed operating and regulatory frameworks. What might these changes mean for patients? Because companies will be able to manufacture a wider range of products more quickly and have the flexibility to scale production up or down as required, they will be able to provide their end-users with a better, faster, more personalised service and produce pharmaceuticals which are currently uneconomical because of small patient populations.

|

|

And what might future product, process and supply networks look like in a continuous manufacturing model? Our research suggests that companies will be able to adopt a range of different supply chain models which can offer more localised production and dynamic replenishment models. They are likely to be characterised by geographically dispersed production networks, supported by more repeatable processes, and the flexibility to adapt production volumes in response to demand. Another key advantage is that fewer production steps will mean that the manufacturing process can be streamlined in contrast to batch-processing which often involves multiple stages taking place across a variety of locations.

|

|

Dr Jag Srai |

However, these continuous manufacturing and supply models do need to overcome some major hurdles. This is a still a very uncertain environment in which both industry and governments are unclear as to the impact this technology will have on industry structures. Within the industrial ecosystem as a whole there is work to be done to change the mindsets of policymakers and regulators to support these new patient-centric business models operating within a clear regulatory framework. Within companies, buy-in is needed particularly from process engineers who are faced with not fully proven technology and quality assurance processes.

But the potential opportunities continuous manufacturing may provide are considerable from the patients’ point of view. And companies could be looking at major cost savings from fewer, smaller plants, reduced capital expenditure and operating costs coupled with significant improvements in yield and more consistent quality. These are interesting times for the pharmaceutical industry. Watch this space.

Capturing Value from Global Networks

In April the Centre for International Manufacturing is publishing a new report outlining its strategic approach to the design and management of global value networks: Capturing value from global networks: strategic approaches to configuring international production, supply and service operations by Jagjit Singh Srai and Paul Christodoulou. (paperback £35.00)

The report will provide the focus for the 18th annual Cambridge International Manufacturing Symposium on Thursday 11 and Friday 12 September 2014. The Symposium will examine the key themes of the new report and the implications for manufacturing, supply networks and corporate policy in the 21st century.

REMEDIES: reconfiguring UK pharmaceutical supply chains

REMEDIES is a new £23m project that includes £11m of UK government funding and which provides an opportunity to reconfigure existing pharmaceutical supply chains in the UK by exploiting the latest technology advances in medicines and patient-centric delivery models.

Part of the UK government’s Advanced Manufacturing Supply Chain Initiative (AMSCI), the project will be led by GlaxoSmithKline, providing major inputs on clinical supply chains, with the Centre for International Manufacturing leading on commercial supply chain and overall research coordination, AstraZeneca focusing on formulation developments and the University of Strathclyde team within the Centre for Continuous Manufacturing and Crystallisation looking at active processing.

CIM will lead the research activity as part of this sector-wide initiative evaluating new technology innovations within the UK pharmaceutical supply chain. Other industrial partners include the major contract manufacturing organisations, equipment manufacturers and technology and system providers spanning the end-to- end pharmaceutical supply chain.

The collaboration also involves key institutional bodies across the UK pharmaceutical ecosystem (skills agencies, user representatives, regulators and health sector specialists) to ensure more adaptive future supply chain models are supported by consistent standards and a unified approach to regulation. Activities will include two sector-wide platform projects focused on the end-to-end clinical and commercial supply chain, and several technology-specific application workstreams.