Thought for food: challenges in the food supply chain

Dr Mukesh Kumar leads research in supply chain resilience at the IfM. He describes how his work is helping to tackle one of this century’s most important challenges: food safety.

According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 600 million people – that’s almost 1 in 10 of the world’s population – fall ill after eating contaminated food every year and of those around 420,000 die.

It seems that every few years a major food contamination scandal erupts – and when it does it is likely to affect large numbers of people. In recent memory, there was the German E. coli-contaminated beansprouts that killed 53 people and affected nearly 4,000 people in total. In China 54,000 babies were hospitalised in 2008 and 6 died from drinking formula that was contaminated with melamine.

More recently, 13 European countries were involved in a different kind of food scandal when horsemeat was substituted for beef in a range of burgers and ready meals. Unlike the other examples, this one posed no risk to public health, but it triggered a highly charged response from consumers who were upset by the unwitting consumption of a type of meat they were either prohibited from eating by their religion or that they were culturally conditioned to avoid.

Why do these incidents keep happening? One of the reasons is that as consumers in the developed world, we expect our supermarket shelves to be stocked with fresh food all year round. To make this possible long, complicated food supply chains have evolved comprising dozens of companies crossing many borders. And therein lies the potential for inadvertent contamination or, as in the horsemeat case, for deliberate fraud.

This is further exacerbated by patchy international standards and the fact that much of the world’s food production takes place in developing countries that may have neither the awareness nor the means to comply with the more stringent food safety practises adopted in developed nations.

Food safety and maintaining public confidence is a complex business – and one in which global supply chains play a critical part. One of the issues we need to understand is the respective roles played in the supply chain by developed and developing nations, and the different challenges they face.

To this end, our research has focused on the UK and India, mapping the supply chains that connect these two countries in order to identify potential vulnerabilities.

India seemed like a good country to study for a number of reasons. Of the developing countries exporting food products to the UK, it accounts for 20% of cases where products are rejected because they fail to meet the required standard.

Agriculture is one of India’s most rapidly growing sectors and research into its food safety practices has been limited. And, although it is the second largest producer of fresh fruits and the sixth largest producer of fish, around 30% of India‘s produce is lost due to contamination or to problems keeping the produce refrigerated at the right temperature across the supply chain. The overuse of antibiotics has also been a longstanding issue in marine exports from India.

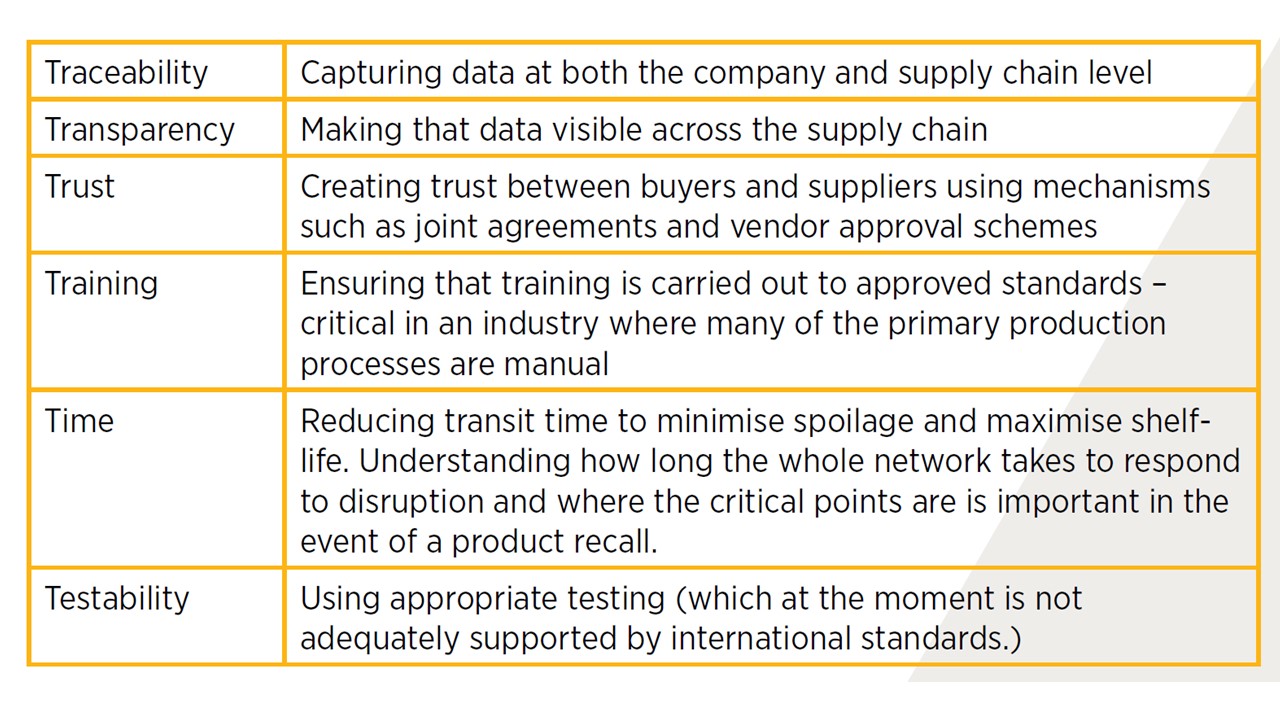

As a leading centre of research into supply chain configuration, the IfM has developed a number of approaches for mapping supply chains and assessing risk. We do this using a combination of desk research, in-depth interviews with companies, site visits and analysis of company documentation. We have also been using what is known as the ‘Six Ts framework’ to examine key characteristics of the supply chain (see table below).

The Six Ts: Defining ways of working that will support food safety and public health.

An improving picture

Our research revealed plenty of signs that firms within the supply chain are making significant improvements to their operations. For example, in order to increase transparency and traceability, the food exporters in India – who largely control the supply chains – are moving away from the traditional Indian supply chain model that uses local traders or wholesalers as middlemen. They recognised that the farmers needed to develop better food safety and quality practices and the only way they could influence the farmers was by having a direct relationship with them.

The food exporters are also increasingly focusing on their core competencies and outsourcing to specialists those activities in which they have no expertise. They are also putting in place better ways of monitoring the performance of these suppliers. All of which represents best practice in the world of food safety.

Interestingly, it is consumer perception – rather than food safety standards – that is driving some of these changes in behaviour. One of the companies we studied has responded to consumer concern over the use of agro-chemicals by using bio-pesticides and bio-fungicides, and by importing water purifiers from Spain to avoid water contamination and to reduce the presence of chemicals to below their permitted levels.

More to be done

Nonetheless, significant challenges remain.

A lack of harmonised international standards is one of the greatest barriers to progress. The current testing regime is also unhelpful. It relies on end-product testing, which is highly inefficient if contamination is happening at the point of production. Companies are increasingly looking at testing much earlier in the product life-cycle when the products are still in the production facilities.

Supply chain traceability is also an issue. The companies we studied demonstrated good practice in capturing data about their own activities, but they typically do not share data with other supply chain partners. Using technology for sharing information was patchy, but there was an increasing recognition of its importance.

Digital solutions

Looking at our results it is clear that research in other areas – such as the use of sensors and big data analytics – could have a vital role to play in food safety.

Digital solutions could allow all the activities that underpin food safety to be managed in real time and to agreed standards across national borders.

Nestlé is sponsoring an IfM PhD student to develop a better understanding of food safety risks, a useful categorisation of the supply chain information needed to manage those risks and the digital technologies needed to capture and analyse that data.

The ultimate aim is to develop a digital food supply chain framework to support food safety in a complex global food system.

This project will be an extremely important next step. Our work so far has enabled us to develop a set of best practices that are designed to help Indian firms continue to improve food safety, customer trust and, by extension, the perception of the food sector in developing countries more generally. However, it also exposed a number of vulnerabilities in these cross-border supply chains and one of the key ways of addressing them is by using new digital technologies and big data.

Find out more

Hear from Mukesh and other experts at the IfM Briefing: Innovation for Food Security and Sustainability

Tuesday 25 June - 17.30-20.00, The Crystal, London

Article orginally produce for Issue 7 of the IfM Review