How sustainable are our online food shopping baskets?

E-commerce has completely changed the way we shop. It’s value for consumers lies in its convenience, and for retailers in its new market potential and powerful sources of data. But how sustainable is it? This is a particularly pertinent question when it comes to food and fresh goods.

Dr Jag Srai, recently appointed as Co-Chair of Cambridge Global Food Security, has been researching these issues with his team in the IfM’s Centre for International Manufacturing. We interviewed Jag to find out more about his work and the considerations for any of us when we click to buy groceries.

Jag, what issues do you see emerging from the transformation of the way we shop, including buying our groceries online?

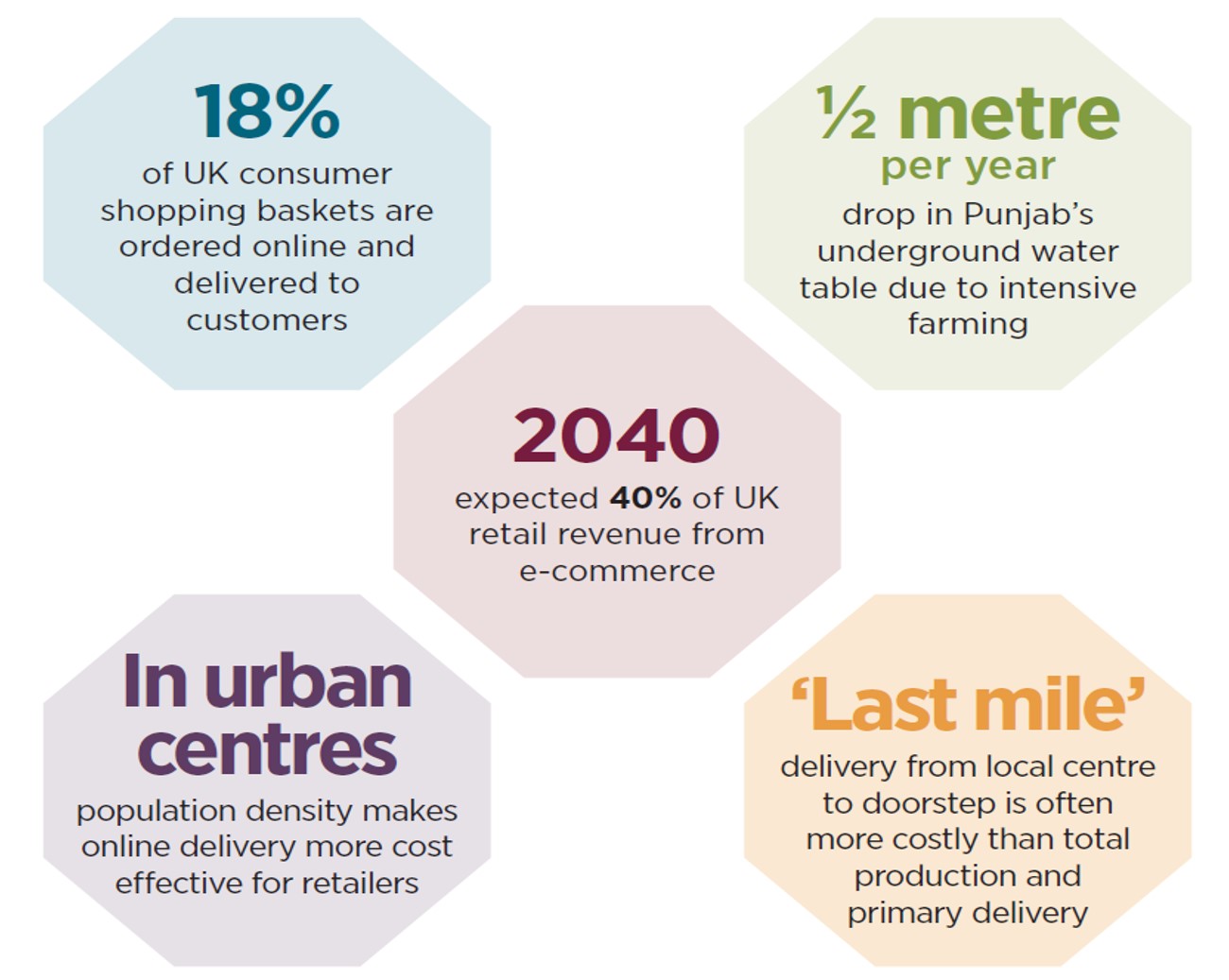

The rapid growth of e-commerce has transformed our behaviour as consumers. In the UK, where e-commerce retail has led all other markets, 18% of consumer shopping baskets are ordered online and delivered directly to our doorsteps. It is anticipated that two-fifths of retail revenue will be online by 2040, with e-commerce becoming the dominant way to shop in major urban centres where market penetration of online shopping is higher.

As part of this transformation, there has been a drastic change in consumer expectations. Many of us as consumers have become accustomed to getting what we want, when we want it, with more choices around product format and delivery mode. In some instances, big retailers have moved towards same-day delivery, sometimes within 2-hour delivery windows in locations where population density makes this cost-effective.

Innovative retailers have developed powerful new ways to engage with consumers. A much more personalised form of interaction is now possible, with the ability to target customised offerings to individuals. For example, rather than a generalised special offer on a physical supermarket shelf, retailers can use data gathered on digital channels to target an individual online shopper with the type of special offer to which they are most likely to respond, on their favourite brand, timed to prompt purchase when they usually place a grocery order.

Despite these undoubted benefits of e-commerce in terms of consumer choice and convenience, there are also many challenges with this new paradigm. Do we need for example to guard against unchecked consumerism without regard for the environment, and to mitigate negative consequences for producers and for the regions from where products originate?

Indeed, beyond the ‘business case’, there are many questions for retailers, producers and across the supply chain including issues of fair-value distribution, waste generated, resources consumed and sustainability of operations and how these might inform sourcing strategies. For the food industry there are of course some specific issues concerning timeliness of delivering fresh produce, and inventory management of products with expiry dates.

How do online food retailers currently decide what they can offer in terms of delivery options?

Any online retailer – however conventional or disruptive – has several strategic decisions to make: What are they going to compete on, and is this reflected in the trade-offs they make between delivery responsiveness, product variety, and convenience? Can they afford to offer delivery in less populated areas, or is it simply uneconomical to do so? How do they address the very real impact of short journeys on vehicle emissions and congestion, particularly in cities?

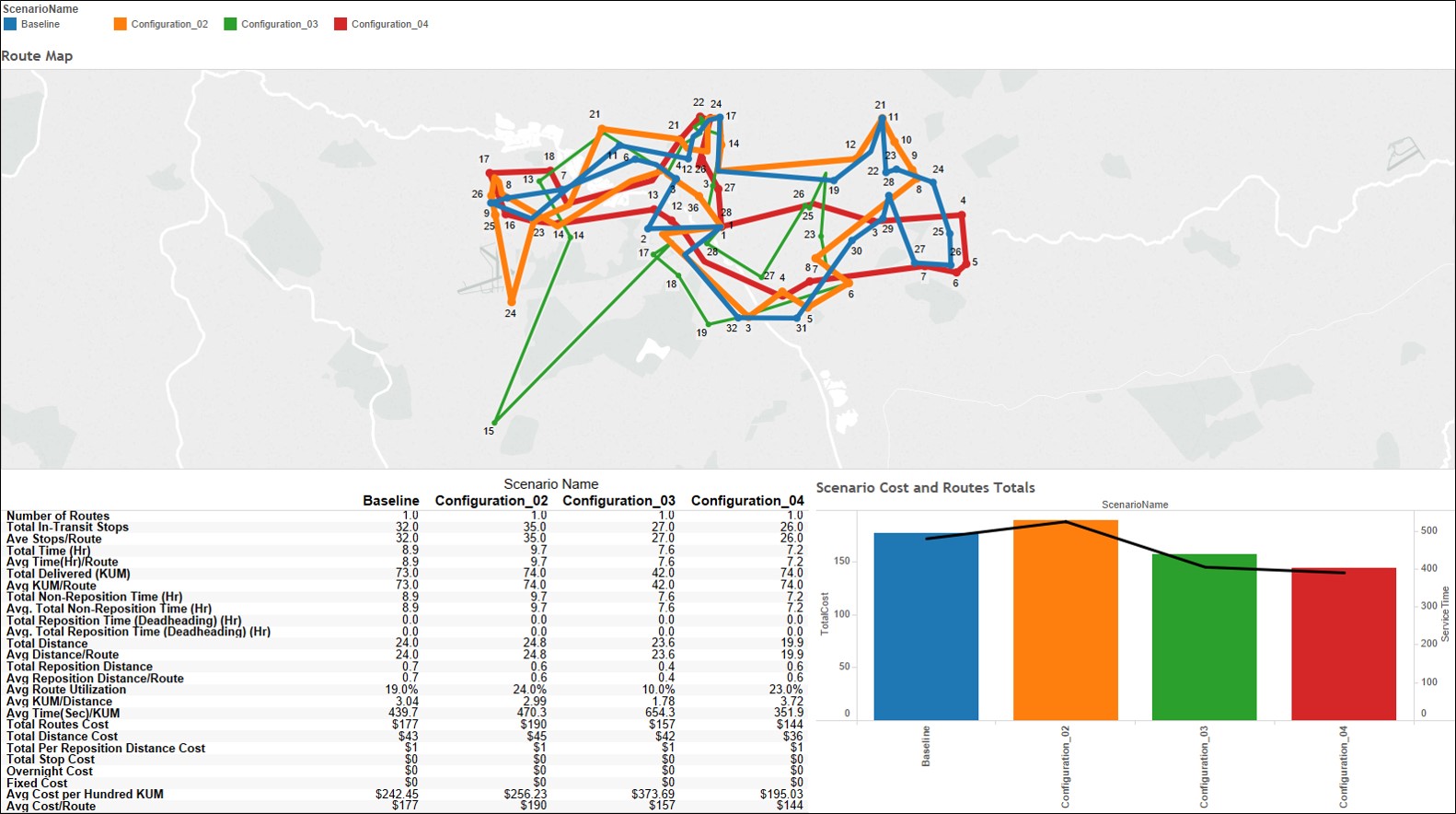

Our research team in the Centre for International Manufacturing (CIM) has been analysing what is termed the ‘last-mile’ of delivery. Analysis of cost data indicates that this very last section of delivery, reaching the door of the consumer from a local consolidation centre, can be higher than the total of production/assembly cost of the product and its primary shipment. The last-mile also creates a significant carbon footprint. We have been modelling optimum transport routes for delivery, using sales data provided by our industrial partners combined with publicly available data on population density for selected postcodes.

This has enabled us to model cost-efficiency for last-mile delivery, taking into account population density in e-commerce savvy areas, where online market penetration drives costs down. We are now extending this work to incorporate solutions that also consider the carbon footprint of delivery options to ensure the sustainability of this delivery model.

New approaches have been developed by an emerging breed of companies including Amazon, Ocado, Uber Eats and Deliveroo, demonstrating that tackling the last-mile logistics effectively in the e-commerce environment requires both new technology capabilities and new business models.

‘Last Mile Modelling’ solutions identify cost effective scenarios for delivery in target locations.

Figure reference: Srai, J.S., Settanni E. (2017), "Is last-mile delivery only viable in densely populated centres? A preliminary cost-to-serve simulation for online grocery in the UK". Proceedings of the 21st Cambridge International Manufacturing Symposium, 28-29 September 2017, Cambridge, UK

https://www.ifm.eng.cam.ac.uk/insights/global-supply-chains/cambridge-international-manufacturing-symposium/

As consumers, when we order our groceries online, how can we know if we are making environmentally-responsible choices with our shopping baskets?

Not easily! Consumers and policymakers are seeking greater transparency and visibility on how our food is produced. In particular, there needs to be much clearer information on whether locations have been exploited for scarce resources, including something many of us take for granted, the sustainable use of water.

If we buy a breakfast cereal, for example, using crops grown in a water-challenged environment, that location has in effect exported its scare resources to us. Water is used both in the production of the food, but also embodied in the product itself, which is being removed from that environment. The scenario that unfolds is that regions where water is scarce are often exporting that valuable resource to regions where there is not the same pressure on water; and this dynamic today is largely driven by financial economics rather than the environmental or in this case the water footprint.

There are also challenges in the supply chain around provenance and the traceability of food produce. As supply chains have become more internationalised, traceability has become more difficult. But there is growing public demand for evidence of where and how a product was made, that it is safe to consume, and—increasingly—whether it was produced in a sustainable way.

What kinds of environmental and social stresses are being caused in regions of the world where product originate, including developing countries?

I visited the Punjab region in April as part of TIGR2ESS (Transforming India's Green Revolution by Research and Empowerment for Sustainable food Supplies) - a GCRF-funded £7.8 million programme, which is seeking to improve livelihoods and farming in India.

The Punjab is a region renowned for lush green fields, and known as the bread-basket of the Indian sub-continent, but is increasingly becoming water stressed. Data from the last decade confirms that the underground water table is dropping by half a metre per year in order to sustain the region’s current food production role. So the much-heralded improvements in yield from cultivated crops comes at the expense of significant overuse of available resources. If this continues, one could project desertification of the landscape within a few decades.

There are social and political consequences too. Some five hundred farmers commit suicide every year in the Punjab (a region smaller than the UK) due to their inability to meet what they perceive as minimum income, despite the over-use of fertilisers, pesticides and water resources. So one of the objectives of the TIGR2ESS project is to support sustainable development through more informed resource and land use whilst also addressing the lot of the marginal farmer so that there are credible alternatives to the current situation of short-term resource depletion in order to generate income and pay debts.

So there’s a requirement to bring together a multidisciplinary approach to address these issues – there are socio-economic aspects as well as the more familiar technology and operational interventions that support the building of scalable yet sustainable supply chains.

How optimistic are you about the prospects for making a meaningful difference through TIGR2ESS?

Our aim is to make a difference through local academic and institutional collaborations, and with specific technology interventions involving farmer-producer organisations, where resources are shared, know-how exchanged and new markets for non-commodity products developed at scale. The farmers are acutely aware of the unsustainable context they are in, and they are passionate about protecting their environment so we have an engaged network of producers, technology developers and local institutions.

How does food waste relate to this pressure on global food supply?

Despite the pressure on food availability in many regions, simultaneously food waste is also a major problem. It can be difficult to assess the scale of food losses and waste, as many studies consider different elements of the farm-to-fork supply chain without necessarily considering agricultural process and avoidable storage losses, production and distribution inefficiencies, retailer write-offs and unused consumer produce.

However, the picture is far from uniform. In the developed world there is greater profligacy at the consumer end – as individual consumers throw a lot of food away uneaten. Whereas in other parts of the world, waste is more likely to happen further up the supply chain, with a complex set of causes including potential for crop failure, problems with moving crop from harvest to efficient distribution, absence of good warehousing and other transport and storage infrastructure.

How do you think technology can be used to address the issues around sustainability and food waste?

Working with our academic and industrial partners, we’ve been exploring waste within food supply chains. It’s important to know where in the supply chain the waste is happening: what proportion of waste happens in agriculture, or post-harvest in manufacture, retail or in the hands of the consumer? Strategies to reduce waste can then be identified, and potential technology interventions to reduce loss or introduce re-use or recycling. With perishable goods, speed is of course a major concern.

CIM is currently participating in three projects funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) exploring several themes around sustainable e-commerce supply, the traceability of organic food products, and the use of novel feedstocks. EIT Food was established as a £340 million programme in 2017 with the University of Cambridge as a founding partner, aiming to change the way we eat, grow and distribute food.

In one of these projects, Green Last Mile Delivery (GLAD), we’ve been exploring more sustainable ways for home delivery tailored to personalized nutritional needs. The project is looking at how online platforms may support personalised product choices and delivery options. When you buy a product, the data gathered about your preferences can help the retailer to better target offers that are more customised to individual preferences. From a waste reduction perspective, presenting consumers with special offers on products as they approach expiry dates, or using ‘nudge’ tactics to influence consumers towards choosing more nutritional or sustainable options for their shopping baskets, is being explored leveraging latest technology developments in predictive analytics.

Digital platforms have the potential to provide new opportunities to connect consumers with their local retailers and farmers, offering personalisation, a more informed shopping basket and less waste.

Consumers too are increasingly better informed and the transparency of sourcing policies and controls to demonstrate authenticity, quality and ethical sourcing practices is becoming part of the requirement of some e-commerce platforms.

Finally, as its new Co-Chair, how do you think Cambridge Global Food Security can help to support greater transparency and sustainability in food supply chains?

The issues we’ve been discussing here are complex and cut across many disciplines, and it is crucial that we bring together interdisciplinary thinking to address them.

Cambridge Global Food Security is one of the University’s eight Interdisciplinary Research Centres (along with Cancer, Conservation, Energy, Infectious Diseases, Language Sciences, Neuroscience and Stem Cells), which are established as cross-School initiatives to tackle interdisciplinary challenges. It has evolved from a Strategic Research Initiative, and now involves around 160 researchers from 24 departments, pulling together research and expertise including crop science, policy, economics, public health, development studies and engineering.

Our role is to use our interdisciplinary research to develop innovative solutions and provide robust evidence to inform the decisions of industry, policy-makers and the public, so that we can address the challenges of feeding a growing world population in a sustainable manner.

For further information please contact:

Dr Jagjit Singh Srai