Business model innovation to solve productivity paradox

New digital technologies are supposed to bring us unprecedented efficiencies and new opportunities for value creation. So why has the productivity of major economies been slowing down over the past 10 years? And in spite of the recent (small) upswing in our productivity figures, why does the UK perform so much worse than its peers? What’s going on, asks the IfM’s Dr Chander Velu, and might it have something to do with business models?

In productivity terms, the UK currently lags around 35% behind Germany, 30% behind the US and 9% behind Italy. These figures make such startling reading that they distract us from the fact that the rest of the world is not doing very well either, most notably the G7 economies. Particularly perplexing is that the sectors contributing most to the slowdown seem to be the most intensive users of information and communication technologies.

This has had analysts scratching their heads and hypothesising possible causes. The aftermath of the financial crisis continues to have an impact on markets. We also know that the inexorable rise of digitalisation has brought with it a number of challenges as well as opportunities: its take-up is being hampered by a lack of skills – particularly in the UK - and while some firms are performing disproportionately well there remains a long tail of SMEs that are struggling to adopt the new technologies. These could all be factors but is there something else going on?

One area that is ripe for further exploration is the need for business model innovation alongside technological innovation. We know that the introduction of new technologies does not - by itself - translate into productivity gains. One of the lessons we have learnt from the industrial past is that when electric motors first replaced steam engines in the US there was very little initial improvement to productivity. It was only when firms completely changed their business processes and corresponding business models that the technology had a significant impact on productivity – and that process took 30 years. Is something similar going on with the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’?

Is how we measure productivity part of the problem?

Productivity is measured at two different levels. Analysts either look at the activity levels within individual firms to improve the efficiency of their processes or they take an economy-wide view to measure economic growth. There are two problems with this approach. Firstly, the firm-level measures focus on improving the efficiency of existing business models and not the effectiveness of the business models themselves. It looks at how value is created and captured – and how efficient a firm is at doing that – and not at the potential changes to the business model in order to deliver new customer value propositions. This is a major shortcoming when trying to understand the productivity of a business model – it needs to take account both of the firm’s and its customers’ perspectives. Studies have shown that firms which place too much emphasis on efficiency (and not enough on meeting their customers’ needs) inhibit their potential to innovate their business model.

The second problem arises from the flipside of that scenario. Digital technologies have, in some cases, so radically transformed the way products are made and sold that it makes productivity for national income growth difficult to calculate. For example, the ‘old’ business model in which a firm creates value and then transfers it to the consumer has been totally disrupted by firms such as Uber where individuals – in this case, drivers – play a key part in the value creation. In other sectors, different models have emerged in which, for example, content is given away free to the consumer with a view to charging corporate customers for advertising.

Towards a new framework for business model innovators

There is definitely something interesting going on with business models. On the one hand, a lack of innovation may be stifling the productivity gains new technologies can offer. On the other, where business model innovation has taken place, it could be affecting our ability to measure productivity properly. If firms are to solve the productivity paradox – and policymakers are to support them in their endeavours – they need to better understand and measure the productivity of their business models and be able to change them accordingly.

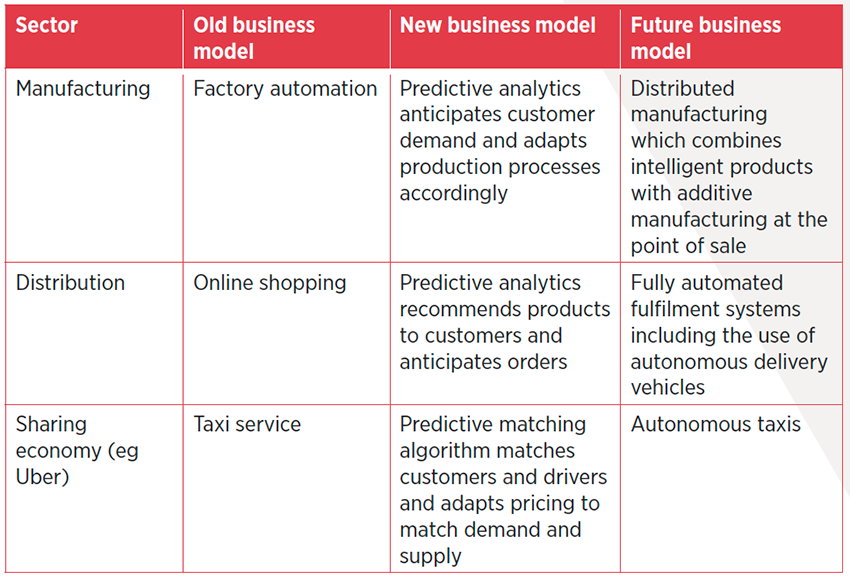

Our research programme is working on ways of doing exactly that. Digitalisation, as we know, is having an impact on virtually every aspect of manufacturing, from 3D printing to last-mile logistics. In order to explore the relationship between business model innovation and productivity and develop some tools to measure its efficacy, we have chosen intelligent automation as a case for illustration. Intelligent automation has the potential to underpin business model innovation in a whole range of different ways (see below table).

Our research programme is working on ways of doing exactly that. Digitalisation, as we know, is having an impact on virtually every aspect of manufacturing, from 3D printing to last-mile logistics. In order to explore the relationship between business model innovation and productivity and develop some tools to measure its efficacy, we have chosen intelligent automation as a case for illustration. Intelligent automation has the potential to underpin business model innovation in a whole range of different ways (see below table).

The possibilities are evident. To date, however, there has been very little research into how business model development can be institutionalised alongside technology development in order to improve productivity.

Distributed manufacturing and the rise of distributed ledger technologies

If we think there are ways intelligent automation can enable business model innovation, we can also see the potential for wholesale disruption of the conventional manufacturing model in which products can be manufactured close to the consumer. Distributed manufacturing presents enormous opportunities for increasing productivity but there are also some significant barriers in its way. If the making of products is delegated to third parties, how can the IP owner ensure they get paid and how can they ensure that the product is manufactured at the right quality and is compliant with any regulations? Some of these issues can be solved by using distributed ledger technologies, a broad swathe of complementary technologies including bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, blockchain, distributed consensus, smart contracts and the associated security-related technologies.

In the future, it is highly likely that many consumer appliances will be IoT-enabled and capable of checking their own quality, integrity and intellectual property. If the appliance is connected to a distributed ledger this data could be recorded and made accessible – securely – to a range of users who would then be in a position to develop new business models and hence drive productivity improvements.

The designers of the appliance - as well as monitoring usage and managing their IP - could check their products’ performance and collect data that could be used to improve future designs. Product comparison firms could rate aspects of performance such as energy use and noise levels. Sales firms could value an appliance remotely by looking at its age, usage and repair history and set up an auction. Regulators could check that the appliances meet safety standards. Custom design firms could develop bespoke parts and appliances to meet the needs of particular demographics, such as the elderly or visually impaired. Rental companies could rent them, offering servicing and upgrades. These connected technologies can also help reduce environmental impact. With over two million tons of waste electrical equipment generated annually in the UK alone, any reduction in waste through better repair and recycling would be helpful.

In its recent Industrial Strategy White Paper, the UK government emphasised that solving the productivity paradox is critical if the UK is to increase the value of its manufacturing and deliver economic growth. The development of digital technologies is creating plenty of opportunities to improve productivity but until firms are able to re-invent their business models we are unlikely to see the real productivity benefits at a national level. For individual firms, those that recognise that technological and business model innovation need to go hand in hand are most likely to derive the benefits from the next production revolution.