Describing skills: The art of the specific

Describing a skill using only one or two words is something we do frequently. But it can create difficulty, because it can imply different things to different people, depending on their experience and context.

When it comes to developing students for transitioning from education to work, this is particularly important… In order to acquire and develop a skill needed for the workplace, it is important to unpick what it involves more closely. Judith Shawcross from the Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge, explains some insights from her research into this.

Can you make a cup of tea? How do you visualise the process? Are you in a familiar kitchen with a kettle? You’re imagining performing a skill, and most likely it’s one you feel you can do fairly easily.

But think about it in a different context. Imagine you are in a forest or up a mountain, and to make tea you first need to light a fire. Maybe you don’t even have matches. In this context, the skill of making tea becomes more complicated and difficult than using a kettle in a functional kitchen, and brewing a drink appropriately. It now encompasses other skills which are challenging in themselves, such as gathering useable firewood, building a fire, lighting the fire, hanging a pot over the fire...

Lost in Translation

Similarly, the ability to perform a professional skill in one context is not always directly transferable to another context. Skill descriptions like ‘computer programming’, ‘data gathering’, or ‘project management’ could differ widely in their precise definition and scope between professions, industries, even between teams or team roles, and in interpretation depending on individual experience.

High-level descriptions of skills are usually inadequate for communicating exactly what is expected. For example ‘project management’ does not convey what exactly someone might be expected to do, especially when the type or size of the project and its context are not detailed.

The limitations of the English language (in which words can have multiple meanings) adds further complication, combined with the practice of different communities adopting words for specific situations. The skill of ‘lacing’ could, for instance, refer to lacing shoes, lacing cables, making lace fabric trimming or lacing beads.

Nuanced meanings in words can also shift in translation between languages, another issue which makes describing skills even more problematic given the increasingly international work sphere.

Skills for Effectiveness at Work

These subtleties around describing skills present a challenge for transitioning from education into work.

We considered this education-to-work transition through the example of preparing students for work experience placements. Students on the IfM’s one-year ISMM graduate programme undertake four Short Industrial Placements (SIPs) as part of their course, each time spending two weeks within a company working on a real and significant issue for that company.

The expected outcome from a SIP is a clear, evidence-based definition and analysis of a problem, and a business case to support the implementation of a solution. From the company perspective, these placements provide real analysis and are often highly praised by the host firm as delivering genuinely useful feedback.

For the students, ‘learning by doing’ is recognised as a key strategy for developing graduates for work readiness, giving them insights into how to adapt and apply different knowledge in diverse contexts.

In terms of skill development, work placements help students develop a broad range of skills, from practical implementation skills for the process-driven aspects of completing the project, through to interpersonal and self-management skills.

To get the most from the placements, students need to acquire some basic skills and understand how they may need to deploy them. We prepare them for their first SIP through an introductory lecture and a series of five different practical industrial problem solving simulations, such as reconfiguring a factory layout to improve operational efficiency.

Break It Into Tasks

A key part of teaching and learning the required skills relies on being able to describe them. Describing tasks involved in performing a skill is a good place to start because a task, and the context in which it is performed, determines the skills required – as demonstrated by our earlier example of making tea.

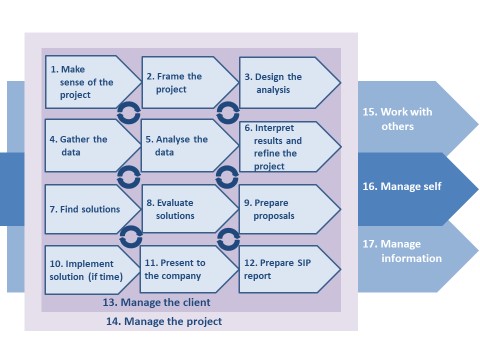

We constructed a ‘Task Framework’ from literature, which provides a way of organising and communicating tasks in a structured way, giving a holistic view of the tasks required to undertake a type of work. This was then tested in multiple ways with the students over their four different SIPs resulting in a Task Framework with 12 process-stages, and five ‘generic’ domains, as shown here. The circular arrows reflect the interconnectedness of the 12 process stages.

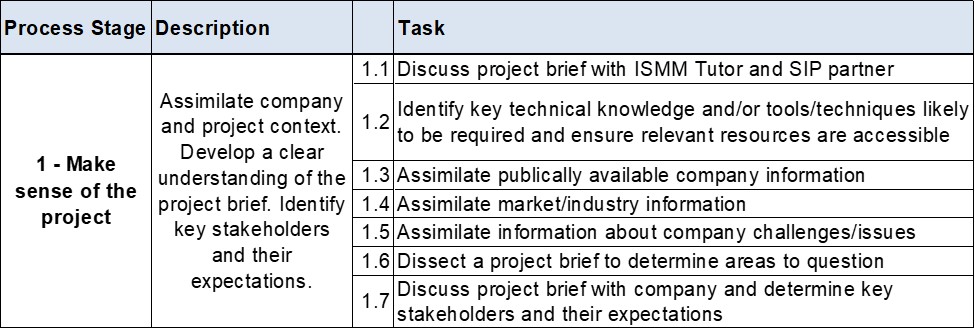

Each of the process-stages (numbered 1-12) includes a number of tasks, which could then be listed. For example, stage 1 ‘Make sense of the project’ can be sub-divided as shown in the table.

Whilst this does not describe skills, it enables skill development by enumerating the tasks which can then be practiced in relevant contexts.

Are People Skills Even Harder to Describe?

We also identified ‘generic task domains’ which span a project. These are i) manage the client, ii) manage the project, iii) manage information, iv) work with others, and v) manage self.

The first three of these (managing the client, the project and information) are tied to project delivery, and closely related to the process stages. They can be described using a similar task-based framework to that shown in the table.

The final two (work with others and manage self) are people-centric domains essential for successful work placements. Describing these is more elusive, but very important, because these are often the areas which present the biggest transition for students moving from education into work.

As with many problems, we tried to tackle this by breaking it down, and we collected data from the students to understand it from their perspective. Could ‘manage self’ be made up of a range of subcategories which were easier to describe? We identified five: health, thinking, being self, ‘being professional’ and ‘managing my work’. Interestingly, around 20% of the student data collected described behaviours and not tasks: for manage self, 16 associated behaviours were identified, with ‘being focused’ and ‘being open-minded’ described the most often.

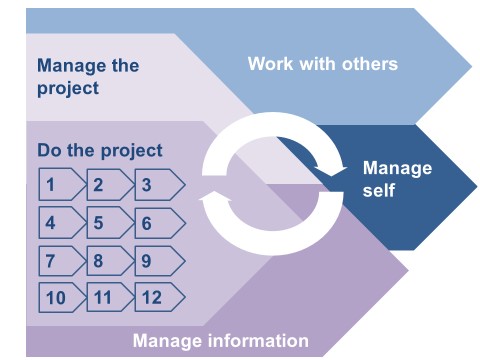

The research found that the generic domains were much more extensive than previously captured, and we needed to modify the Task Framework to reflect this, as shown. In this version, the three purple domains are closely interlinked and are delivery-centric, whilst the two blue coloured domains are people-centric and underpin delivery. The large circular arrow depicts the domain interconnectedness.

Transition to Work

Why is this so important? Why in particular does it help to describe the ‘generic’ interpersonal and self-management skills?

Students find themselves needing to make a significant adjustment to their sense-of-self as well as understanding the expectations that others may have of them when they move into a professional sphere of work. Through their years in education, they will usually have been in a controlled environment, been accustomed to working mostly with people their own age, and had a set of clear expectations focused on a single outcome (passing an exam or course). Young people have developed their sense of identity within this context. Switching to a professional environment, with less clarity around expectations, a wide range of people in terms of age and experience and less clearly measured ‘success criteria’, requires a shift in a graduates’ self-perception.

In addition, academic courses such as Engineering tend to cover neatly defined, bounded problems with clear objectives and sufficient data. Workplaces rarely work in the same way. Problems are typically ill-structured and complex, and often have vaguely defined, unclear goals. These will usually have non-engineering success standards and constraints. So graduates need to make a significant adjustment, requiring personal flexibility and adaptability.

Industrial work placements are used in a variety of ways in different educational settings and help to give students a deeper insight into this significant change in expectations. As such, work placements are widely recognised as an effective method for helping students bridge this gap.

Finding better ways to describe the skills needed for work placements should help both University staff and students to prepare for and ensure that placements are good learning experiences, as well as better equipping them for the transition from University to work.

In particular, adequately describing the generic aspects of the work Engineering graduates do in industry has the potential to significantly improve Engineering Education because it will enable these aspects to be communicated, taught and assessed.